National Security Exception as A Defense in Investment Treaty Arbitration — A Look into Huawei v. Sweden

Xueyu Yang and Zeyu Huang1

Ⅰ

Introduction

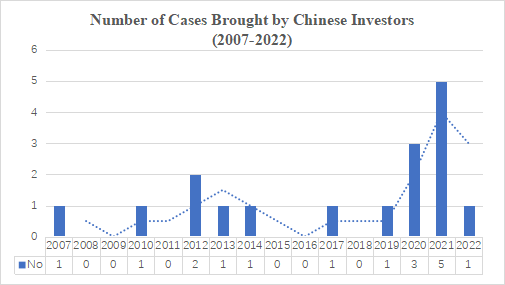

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, the Chinese arbitration community has witnessed an eye-catching explosion of investor-state arbitrations initiated by Chinese investors — nine treaty-based cases have been commenced or brought to light since early 2020.2 This is significant because before 2020 there were only eight treaty-based cases in total. What is more interesting is that the cases brought by the investors domiciled or having residency in the Greater Bay Area (GBA) account for 10/17 of the total cases initiated by Chinese investors against foreign host states.3

Ⅱ

National Security Exception: Is It a Legitimate Excuse or Disguised Protectionism?

Ⅲ

A Look into Huawei v. Sweden

Ⅳ

Conclusion

【Scroll the screen to see more annotations】

1 Xueyu Yang is a partner of Hui Zhong Law Firm based in Beijing. Ms. Yang has particular expertise in handling complex contentious matters involving multiple jurisdictions. Ms. Yang has advised both domestic and foreign clients in proceedings conducted at the ICSID, PCA, ICC, HKIAC, SIAC, CIETAC, BAC and different levels of domestic courts including the Supreme People’s Court of China. Dr. Zeyu Huang is an associate of Hui Zhong Law Firm based in Shenzhen. Dr. Huang holds LL.B. (Renmin University of China Law School), and LL.M. & Ph.D. (University of Macau). He has advised both Chinese and foreign clients in proceedings conducted at the ICSID, HKIAC, SCIA and several levels of domestic courts in the People’s Republic of China. Both authors are currently representing clients in ongoing ICSID arbitration proceedings. The authors may be contacted at: huangzeyu@huizhonglaw.com.

2 Xueyu Yang & Zeyu Huang, ‘Protected Investor and Investment – A Perspective from the Greater Bay Area in China’ (2022) 25(1) International Arbitration Law Review 1, footnote 8, at 2-3.

3 Yang & Huang, supra note 2, at 3-4.

4 Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. v. Sweden, ICSID Case No. ARB/22/2, 21 January 2022 (Date Registered) (hereinafter “Huawei v. Sweden”).

5 See Continental Casualty Company v. The Argentine Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/03/9 (hereinafter “Continental Casualty v. Argentina”), Award, dated 5 September 2008, para. 175. See also Ji Ma, ‘International Investment and National Security Review’ (2019) 52 Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 899, at 907.

6 See e.g. Continental Casualty v. Argentina, ibid, para. 175 (“As to ‘essential security interests,’ it is necessary to recall that international law is not blind to the requirement that States should be able to exercise their sovereignty in the interests of their population free from internal as well as external threats to their security and the maintenance of a peaceful domestic order.”).

7 UNCTAD, The Protection of National Security in IIAs (United Nations 2009), UNCTAD/DIAE/IA/2008/5, at 3.

8 See UNCTAD, ibid, at 26.

9 See Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. US), [1986] ICJ Rep 14, Judgment of 27 June 1984 (Merits), at 95 (considering that “[e]ven if two norms belonging to two sources of international law appear identical in content, and even if the States in question are bound by these rules both on the level of treaty-law and on that of customary international law, these norms retain a separate existence.”).

10 While the majority of free trade agreements (FTAs) are equipped with national security exceptions, not many BITs contain such exceptions. See UNCTAD, supra note 7, at 3 (the survey conducted in 2009 showed only 12 per cent of reviewed BITs included national security exception clause.); Karl P. Sauvant et al., ‘The Rise of Self-Judging Essential Security Interest Clauses in International Investment Agreements’ (2016) 188 Columbia FDI Perspectives, at 1 (only 222 of 1861 (i.e. 11.9%) IIAs concluded by 90 countries contained self-judging national security clause before early 2016.).

11 See UNCTAD, supra note 7, at 34 (“[…] customary international law provides justification for States to derogate from IIA obligations, even when it is not expressly mentioned in the treaty.”). See also Willian W. Burke-White & Andreas von Staden, ‘Investment Protection in Extraordinary Times: The Interpretation and Application of Non-Precluded Measures Provisions in Bilateral Investment Treaties’ (2007) 48 Virginia Journal of International Law 307, at 324.

12 See UNCTAD, supra note 7, at 36.

13 See ibid, at 81-96.

14 See OECD, Freedom of Investment, National Security and “Strategic” Industries: An Interim Report, approved by the OECD Investment Committee on 30 March 2007, at 56-57. China and several other non-OECD countries participated in the discussions leading to the OECD Report.

15 This section is based on Huawei’s Request for Arbitration dated 7 January 2022. As of the date of writing this article, Sweden hasn’t made submissions on merits yet.